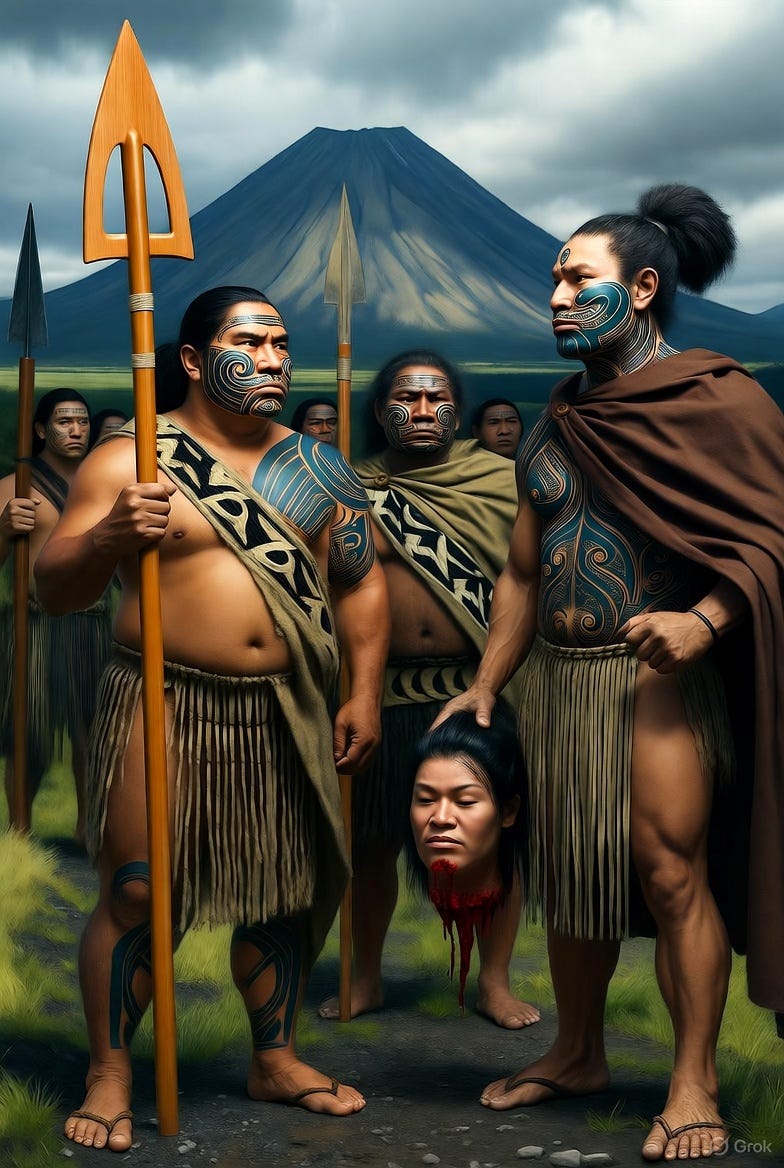

From savagery to structure

How colonisation ended cannibalism in New Zealand

Before European contact, life in New Zealand was dominated by tribal warfare. Entire generations grew up amid battles fought for revenge, “mana”, and territory. Captives could be enslaved or killed, and in a lot of cases, eaten. Cannibalism, recorded in both Māori oral histories and early European journals, was a grim reality of pre-colonial existence.

A…