Were cultural directives a factor in the Mount Maunganui disaster?

The landslip at Mount Maunganui last week should not be dismissed as an unavoidable act of nature. Extreme rainfall was the trigger, but triggers only cause catastrophe when underlying conditions allow failure. In this case, those conditions may have been shaped by human decisions made years earlier. Homes were destroyed, vehicles and infrastructure were buried, and lives were lost. Emergency services and search and rescue teams were placed in danger responding to a disaster that unfolded in minutes. Sympathy for those affected must come first. But sympathy cannot be allowed to shut down scrutiny when public safety decisions may have had a part to play in such a deadly outcome.

It is well established that mature trees play a crucial role in slope stability, particularly on steep coastal land like Mt Maunganui. Deep root systems bind soil layers together, slow runoff, and reduce the likelihood of catastrophic failure during prolonged or intense rainfall. English Oaks and other large exotic trees are especially effective in this role due to their extensive, deep penetrating roots. For decades, these trees stabilised sections of Mt Maunganui not because of symbolism, but because they functioned as natural engineering.

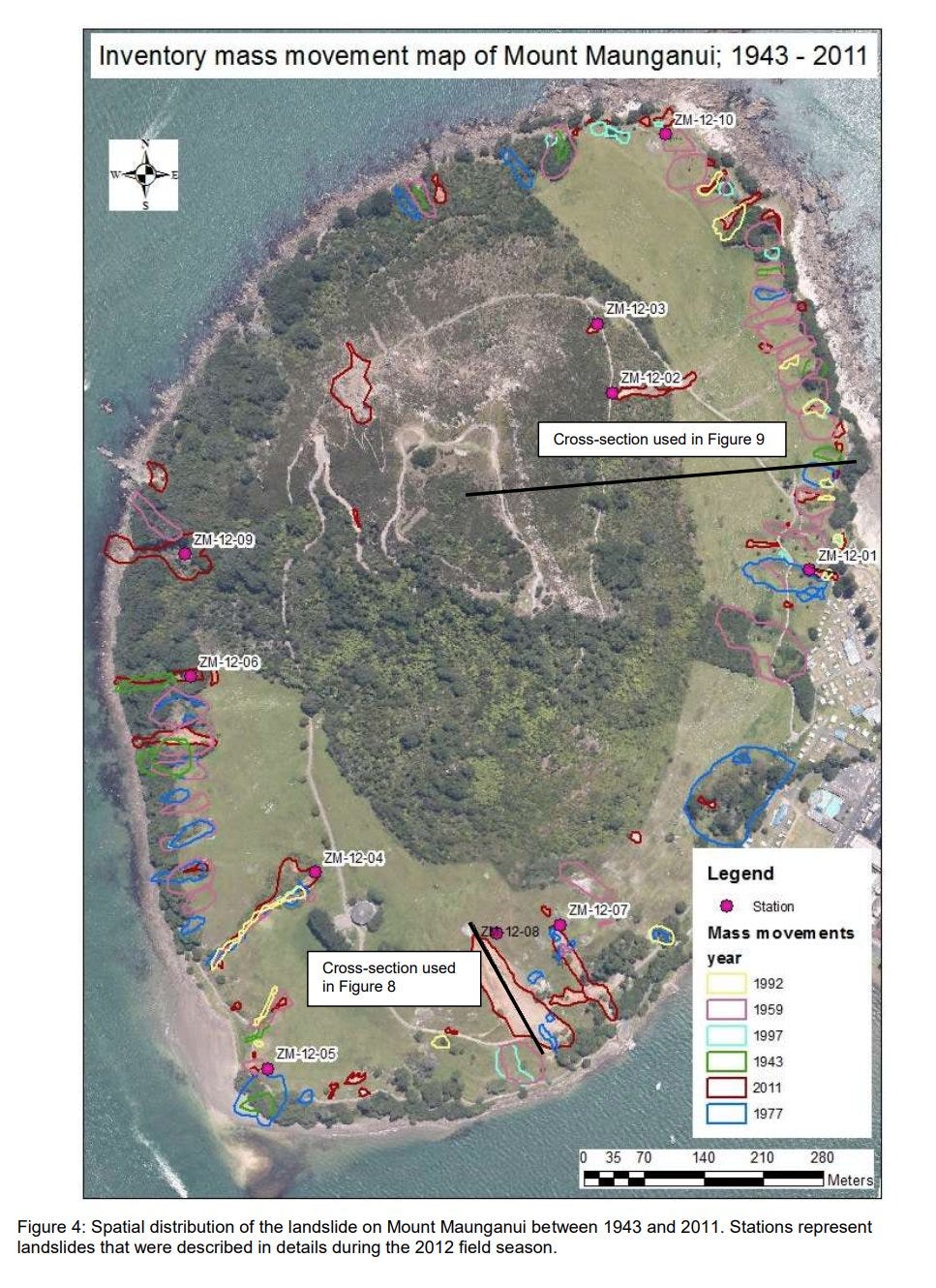

During the January storm from the 16th to the 22nd, a clear regional pattern emerged. The worst slips occurred on steep, exposed, or recently disturbed slopes. Areas with established vegetation were consistently more resilient. This is not ideology. It is a geotechnical reality.

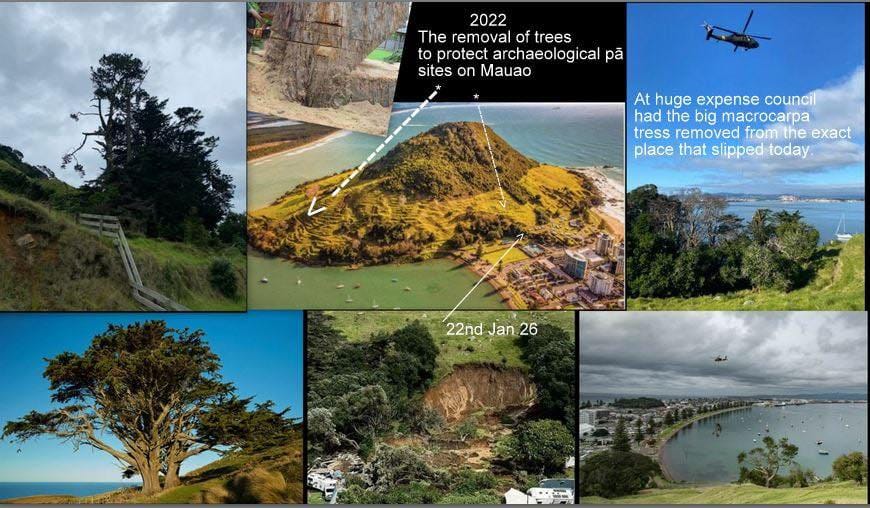

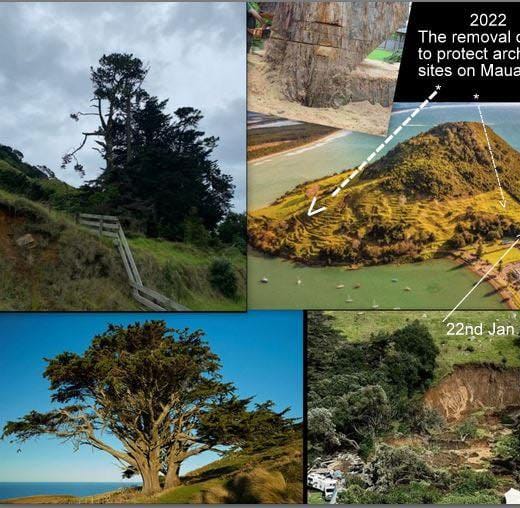

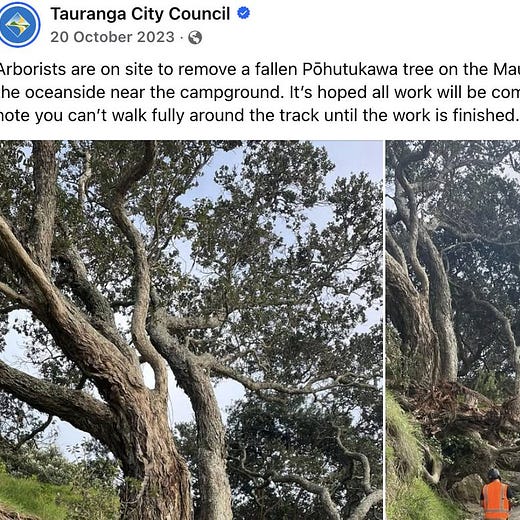

Despite this, in June 2023 Tauranga City Council approved the removal of eight large exotic trees from Mt Maunganui, including a Holm Oak, pine, poplar, chestnut, and macrocarpa. The work involved helicopters and mechanical disturbance on steep terrain. At the time, the council itself acknowledged that such disturbance could trigger slope instability. The risk was neither unknown nor theoretical. It was recognised and accepted. These trees were not removed because they were unsafe, diseased, or failing. They were removed to comply with the 2018 Mauao Historic Reserve Management Plan, which mandates the progressive removal of exotic species to restore the maunga to a culturally preferred ecological state under the direction of the Tupuna Maunga Authority.

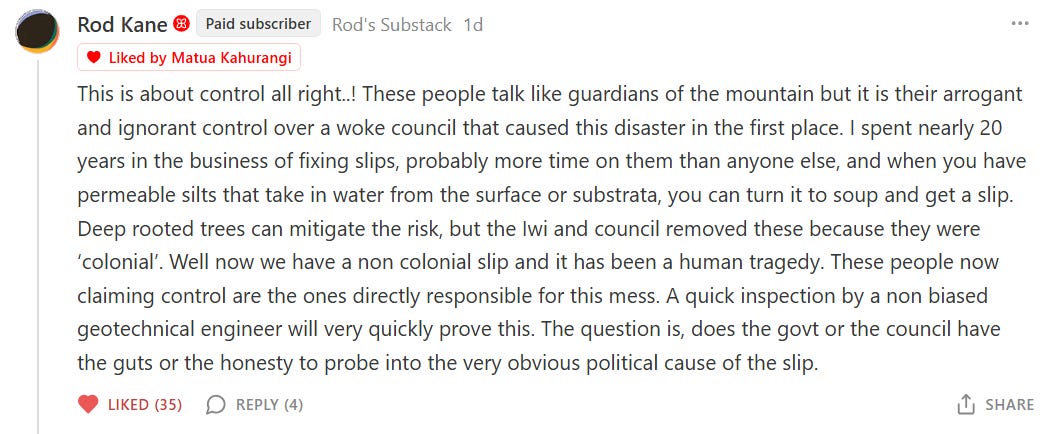

This is where serious questions must be asked. If mature, stabilising trees were removed primarily because they were considered culturally inappropriate under a Māori worldview, then cultural ideology may have been allowed to override physical risk management. This is not an attack on Māori people. It is a challenge to Māori authority when it exercises decision-making power over land that directly affects public safety. Tikanga does not anchor soil. Mātauranga Māori does not replace root tensile strength. Cultural belief does not prevent water saturation during extreme weather. Native replanting was offered as reassurance, yet saplings take decades to provide equivalent stabilisation. That long vulnerability gap was known. It was accepted. And those living below Mt Maunganui were never meaningfully consulted on whether they were willing to bear that risk.

After 9:30 am on January 22, 2026, a major slip occurred above Adams Avenue, burying campervans and an ablution block, destroying property, and costing lives. No serious observer claims that tree removal alone caused the landslip. Extreme rainfall was the trigger. But it is equally irresponsible to pretend that removing deep rooted trees from a steep slope played no role at all. Decisions that reduce slope resilience increase the likelihood of failure when severe weather arrives. That is how cause, contribution, and consequence work in the physical world. If Māori governance bodies influenced or directed these removals, then they must also be subject to accountability when outcomes are deadly. New Zealand has become deeply uncomfortable questioning Māori authority. But gravity does not care about politics, culture, or ideology. Mt Maunganui is not a shrine floating above reality. It is soil, rock, and water. When belief is placed above engineering, the consequences are not theoretical. Sometimes, they cost lives.

Questions that need answering

Public agencies often reassure communities that management plans are evidence based and risk aware. If that is the case, then the following questions deserve transparent answers:

Were geotechnical assessments carried out specifically on the slopes above Adams Avenue before tree removal?

If public authorities are confident their decisions were sound, then they should have no issue answering some very basic questions.

Was the directive to remove exotic trees from Mt Maunganui driven primarily by Māori cultural policy rather than geotechnical advice?

Did cultural restoration objectives override, or take precedence over, slope stability and public safety considerations?

Were iwi or Māori governance bodies involved in directing or approving the removal of mature trees on steep slopes above residential areas?

If so, what responsibility do those bodies accept for assessing physical risk, not just cultural appropriateness?

Were alternative Māori informed approaches considered, such as retaining large stabilising trees until native forest could provide equivalent structural support?

Was mātauranga Māori applied in a way that accounted for extreme weather events, climate change, and the physical role of deep rooted trees in whenua stability?

And finally, if cultural directives influenced these decisions, why has there been so little public discussion about the risks that came with them?

These are not hostile questions. They are necessary ones. When cultural authority intersects with land management and public safety, accountability must apply to everyone involved, regardless of status or worldview.

If the answer to any of these questions is no, then the landslip demands more than sympathy. It demands accountability.